An Extract from the KENYA TODAY magazine, Vol. 5 No 3 dated September 1959, pages 6 to 8.

Mapping Kenya's rugged north

By Major J. Dodman

To be washed out of a wadi by a 30-foot wall of water, working for weeks on end in some of the loneliest parts of the world is not everybody's idea of a steady job. But these were all in the day's work for 89 Field Survey Squadron, Royal Engineers, based on Nairobi.

It was the Mau Mau menace that brought the Squadron into being in 1953. The then existing maps of Kenya were all small-scale and there were a lot of gaps. The Squadron had to produce detailed, accurate maps of the troubled areas quickly. It did.

By the end of 1956 their work was done—or so they thought. Then they were given a "little" survey job in Kenya's Northern Province. Other pieces were added to their commitment until it amounted to putting nearly 90,000 square miles (just about the area of the United Kingdom) on to a 1:100,000 up-to-date and reliable map.

And even that sounds reasonable enough—unless you know Kenya's Northern Province. The population density is "between one and two persons per square mile"; distances are measured in time between waterholes, rather than miles; there are very few roads and no tarmac—to go from here to there probably means blazing your own trail.

Until the South African Army surveyed the area during the war, maps of

the Northern Province were all 1:1,000,000 and expensive, in that you

got a lot of blank spaces for your money. The South Africans did an

excellent job but it was a job done in a hurry and at a scale of

1:500,000. There were still a lot of blanks.

So the five officers and 80 other ranks of 89 Field Survey Squadron pitched into the job and into the wilderness. The work itself meant doing everything from setting up a theodolite in Ethiopia to printing a perfect five-colour map in Nairobi.

First step was aerial photography of the area from 40,000 feet. Much of the work was done by the R.A.F., the rest by charter firms. The Squadron's surveyors took the prints, pin-pointed a single feature and fixed the position by taking astronomical sightings—astro-points. This put the tree on the grid, as it were.

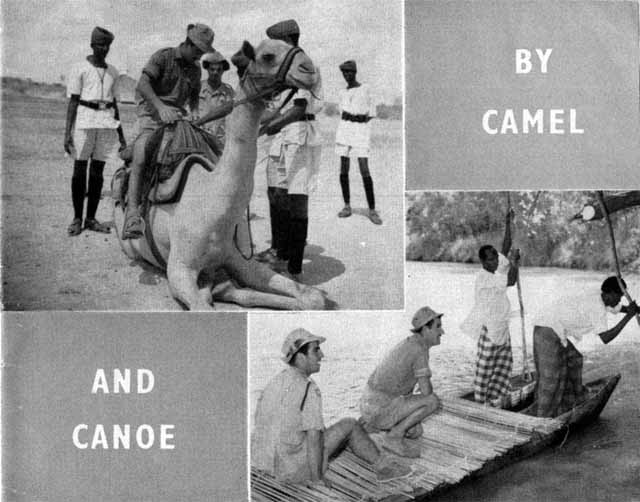

In essence, one of the jobs of a typical five-man party is to go and find a particular tree in the middle of nowhere. Exactly how to get there is one of the things to find out. It might mean leaving the truck and taking to a camel or dug-out canoe. It could mean hastily getting out of the way of a herd of elephant or losing all the food, except unopened tins, to a wandering column of safari ants. It will certainly mean seeing a large variety of wild life, anything from giraffe to the neon-bright blue-and-red Kavirondo lizard.

Suppose the site for one of those astro-points—the position of the lone acacia on the photograph—is somewhere near Garissa. This is a relatively easy one. . . .

On the banks of the Tana River, 250 miles north-east of Nairobi, base camp was established in a little clearing on the bank opposite Garissa. There was a marquee, sides rolled up except for one end used as an office, a neat enclosure made of steel racks containing vital vehicle spares, a couple of tables and a few camp stools. For the amenities there was a shallow scooped-out hearth where a wood fire blazed between rough stone sides, and a radio set. By way of luxury, there was an improvised shower. Its palm-frond screen had fallen down on the only side that mattered—the one facing the footpath to the village close by—but nobody bothered.

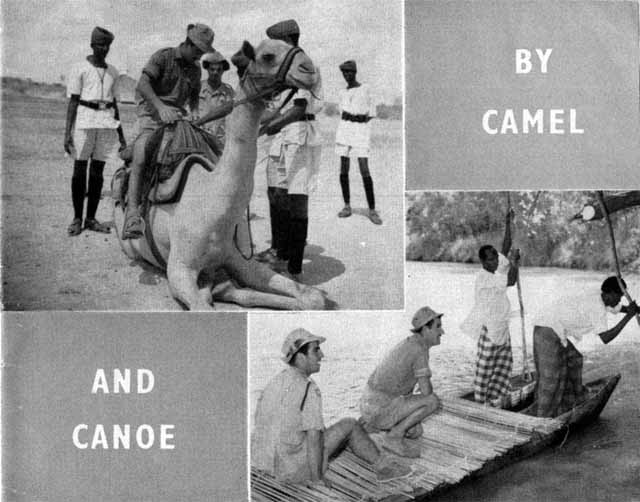

Basic food is "compo" or its tinned equivalent. There is cash available for buying fresh items locally, but more often than not there is nothing to buy. Meat is another matter. There is plenty of small game in most areas and the unit Safari Club is licensed by the Kenya Game Department to operate for food—not for fun.

But that is not the end of it. Out of the banana trees down by the river walks Sapper Alan Bate, proudly waving a ten-inch catfish. He caught it on a bent piece of compo¬wire, sharpened with a nail-file. Lance-Corporal Douglas Witt, a driver, one of those invaluable characters who knows these things, says that it is good to eat. In minutes, he has it skinned and in a pot. Base camp applauded his driving skill, too, when he arrived at Garissa with three plump Guinea fowl. He said he had had the bad luck to run into them when rounding a corner.

So it's Guinea fowl for supper, a night on a camp bed under the stars

and tinned bacon for breakfast before the field party—with the aerial

photograph with an acacia on it—sets out.

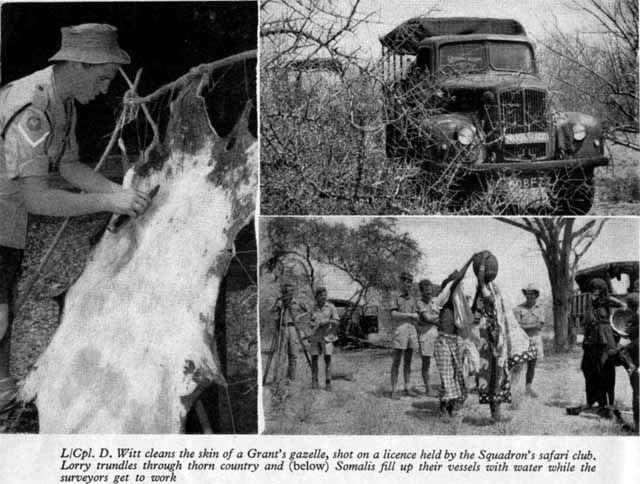

Two surveyors, three drivers, rations, petrol, water and instruments travel in two three-tonners and a Land Rover. They may be out for three weeks. Dust billows up, miles go by. Out come the compasses and it's into the scrub. Twenty-eight-year-old Sergeant Alan McVeagh, a qualified surveyor and in charge of the party, halts the trucks under a tree—the tree.

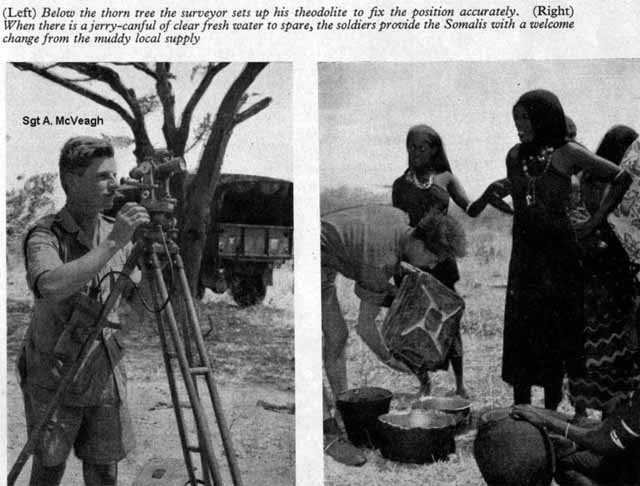

In minutes the drivers have a fire going and there is a "brew" on. The light begins to fade and the surveyors set up their theodolite. As the first stars twinkle, they set to work. Down go their calculations in a little book. As a check, they will take more sightings the following night. Then next morning will see them putting whatever scanty local information there is, on to the photograph. There are no roads, no towns and very little else on the 140 square miles covered by this photograph. They can only add such notes as "camel track; sand; thick bush impassable to motors; many seasonal rivulets" and the position of three holes they have established.

Nairobi is the scene of the next phase. To dismiss an enormous amount of applied technical skill and many complicated processes in a few words, the field work is put on to paper. The map has begun to take shape. Then field parties go out again. This time to check the accuracy and to ensure that all possible detail had been included.

The rest is a lot more skill, patience and concentration. The result is a series of coloured sheets of paper useful not only to soldiers, but to farmers, travellers, and policemen; maps on which man has noted a few more facts about himself and his world.

In its 30 months' work, 89 Squadron has done 100 per cent of the field work, 70 per cent of the compilation, 50 per cent of the drawing and 30 per cent of the printing. Not bad going . . . even if it had been tarmac all the way.

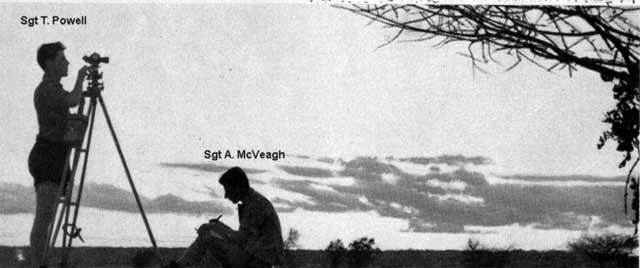

Two surveyors, working from a point established by the Survey of Kenya, check details to make sure that everything has been included.

As soon as the stars begin to shine, the surveyors get to work on an astro-point.